The World Health Organization has declared an international public health emergency as a disease linked to the Zika virus is spreading across Latin America that is expected to infect 3-4 million people in the region over the next 12 months.

The Zika virus has been known about for nearly 70 years. The virus was discovered in 1947, in a rhesus monkey in the Zika forest near the shore of Lake Victoria in Uganda. Over the next five years, Zika was documented in a handful of people across Africa and Asia although it wasn’t of great interest to scientists. The virus appeared to only cause mild flu like symptoms and there were no reports of massive outbreaks. Many dangerous new pathogens had also jostled for global attention. Since Zika was discovered more than 300 contagious diseases have newly emerged or re-emerged in populations that had never been exposed to them, including HIV/AIDS, SARS, Ebola and antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Source: Vox (2016)

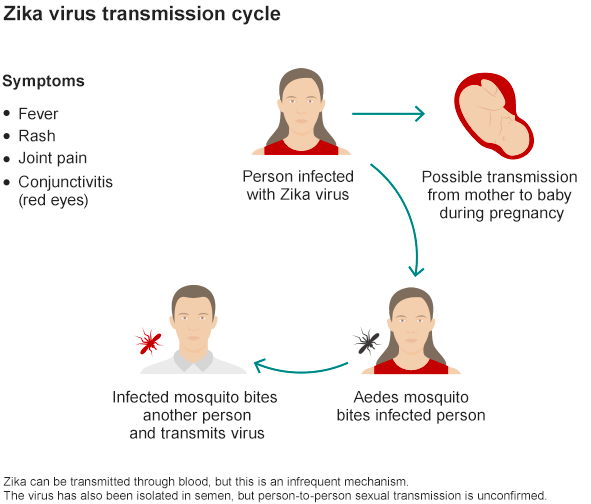

Resurfacing in Brazil last year, the Zika virus has now infected more than 1 million people to date. 80% of the people affected feel no symptoms at all, while others experience mild symptoms such as fevers and rashes. The virus remains in the blood for about a week. But now we’re learning that when pregnant woman contract Zika they pass it on to their fetuses, which in turn can create birth defects. Microcephaly is a birth defect that involves incomplete head and brain development. This can lead to mental dysfunction and a shorter life expectancy. Public health officials in Latin America and the Caribbean are cautioning women to delay any plans to get pregnant. The Centers of Disease Control and Prevention in the United States are also advising people to delay their travel plans to the region this year.

Source: BBC News (2016)

There is currently no vaccine or medication to cure and treat Zika. Infectious disease experts say a safe and effective Zika vaccine is ‘probably three to 10 years away even with accelerated research. The only way to avoid catching Zika is to protect ourselves from the Aedes Aegypti, a mosquito responsible for spreading this virus as well as dengue, yellow fever, chikungunya and malaria. Large-scale campaigns of spraying synthetic insecticides and eliminating standing water are expensive and imperfect, especially as mosquitoes are becoming more resistant to many of our best chemicals. Public health officials around the world say that our best strategy is to avoid contact with these mosquitoes by using repellents.

Naturally extracted as well as being a powerful, effective pesticide, neem has evolved from being a ‘traditional’ medicine to the subject of studies showing its effectiveness in reducing the transmission of mosquito-borne diseases. Neem has demonstrated anti-feedancy, fecundity suppression, ovicidal and larvidical activity, growth regulation and repellence against 500 different insect species (including mosquitoes). As opposed to synthetics, neem-based pesticides have multiple modes of action against insects, and therefore rarely induce resistance. Immune to resistance, entirely biodegradable and cost effective, organic insecticides such as neem are valuable solutions to this public health issue.