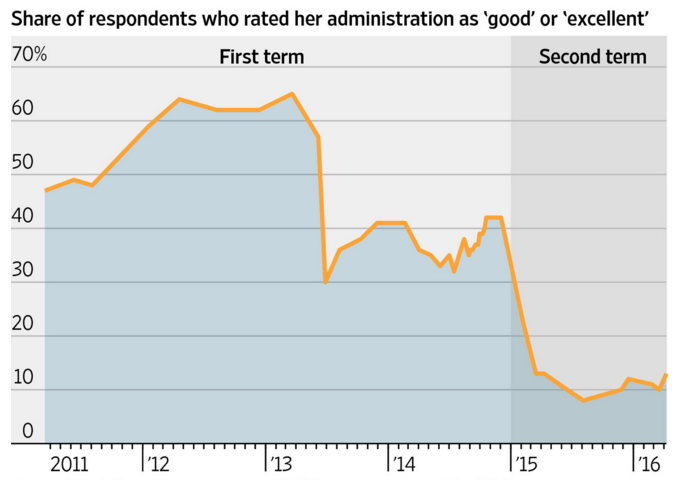

Just over a year after her return to power, President Dilma Rousseff finds herself facing impeachment after the lower house of Congress voted to begin official proceedings late on Sunday evening. With a comfortable two-thirds majority for impeachment (367-137), an approval rating caught in single digits and celebrations erupting on the streets as the results came in, the country is sending a very clear message – ‘Goodbye Dilma’.

Famed for saving a lost generation of Brazilians through a comprehensive series of social development schemes in her previous term, Rousseff and mentor Lula da Silva cut ‘chronic poverty’ by 75% from 2004 to 2012. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization even erased Brazil form the World Hunger Map in 2015. Although Rousseff’s populist mantra and solid support in rural areas ensured her re-election in 2014, allegiances in the Brazilian electorate are now changing. With the combination of maintaining drastic levels of social funding at a time when government finances are under pressure, alongside a myriad of corruption scandals revealed across her administration, Rousseff’s impeachment has effectively been fast tracked.

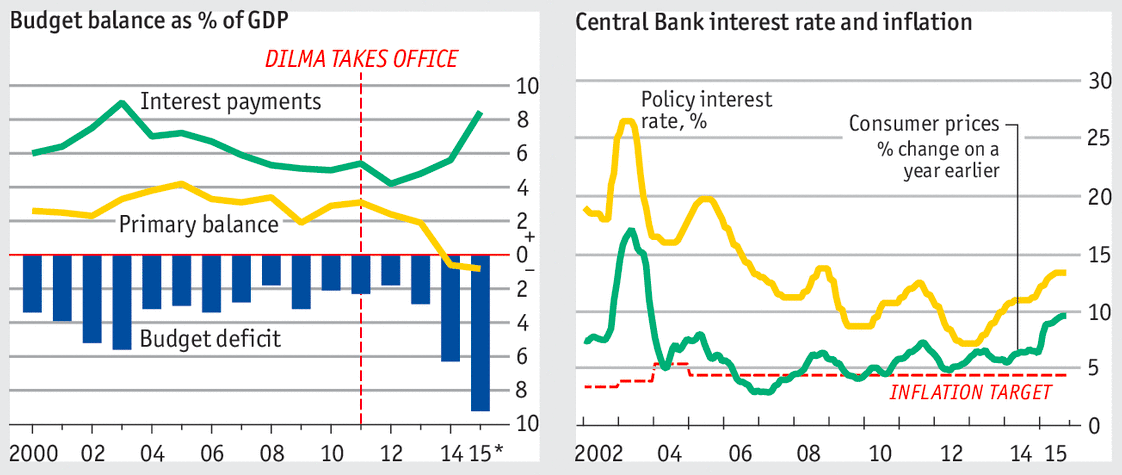

Ready for New Fiscal Direction in Brazil

Source: The Economist (2016)

While roughly 70% of the public support impeachment, a sizeable proportion of the 54 million people who voted for her in 2014 buy into rhetoric that the proceedings constitute a coup from the country’s rightist forces. Although corruption allegations against her are less severe than many of the Supreme Court parliamentarians supervising her judgement, the Supreme Court itself is largely comprised of nominees from the President’s own Worker’s Party. In reality, the vote was fully constitutional, conducted in plain sight of the media and executed with the approval of all necessary stakeholders – making this process a major win for Brazilian democracy.

The Tables Have Turned for Dilma Rousseff

Source: Wall Street Journal (2016)

If a simple majority of the Senate votes to begin an impeachment trial, Rousseff will be removed from office for a minimum of 180 days. These days are vital for Vice President Michel Temer, Rousseff’s likely successor, as he prepares to shoulder the weight of leadership during this transitional period. On financial issues, the interim President Temer would be better prepared to address challenges within the Brazilian economy. To restore confidence, Temer would first need to reduce the budget deficit (which has ballooned from 2.4% of GDP to 10.8% since Ms Rousseff first took office in 2011). That would require a combination of spending cuts and tax hikes. His own Democratic Movement party (PMDB) is centrist in nature and has maintained an impressive track record of supporting tighter fiscal austerity and privatisation programmes that strengthened the country’s economy in 1990. While ethically challenged, Temer is a man that means business. The vote he and his supporters orchestrated to oust Rousseff relied upon consensus across all political parties – just as he would have to do in government to secure his own position and avoid a further constitutional crisis.

Even with his eligible credentials, Temer is merely a short-term solution. Brazil has seen enough corruption scandals to even entertain the notion of a tainted presidency right from the offset. 60% of the population would like to see both Rousseff and Temer resign during the impeachment proceedings. Gaining significant momentum over the last year, the opposition is now calling for a constitutional amendment that enables a mid-term election for the first time in the country’s fervent history.

If this happens the field of presidential hopefuls will most likely be focused on three candidates – Aécio Neves, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and Marina Silva. Neves is a pro-business candidate with excellent proficiency in fiscal policy who narrowly lost to Rousseff in 2014. Rousseff’s mentor and presidential predecessor Lula da Silva has hinted at his run for president in the midst of his own range of criminal allegations. If the corruption scandals render Lula unviable, many left-wing legislators will turn to Marina Silva, the popular outsider candidate who ended up third in the 2010 and 2014 elections.

What does Rousseff’s impeachment mean for Brazil? This process will trigger the reforms necessary to further develop and fulfil the country’s vast and impressive potential. Brazil is on the verge of establishing a new leadership structure that will be responsible for restoring economic growth and further strengthening the country’s macroeconomic infrastructure. Despite the volatility and uncertainty experienced in recent months, this is a significant step towards driving social and economic performance in Brazil for the long term.