Brazil is a country steeped in superlatives. The large and diverse geography, commodity resource-base and economic dynamism over the past quarter century have transformed the country into one of the world’s largest economies and the recipient of some of the highest levels of foreign direct investment (FDI). Although akin to other emerging markets, the pace of transition in the country over the past decade has been volatile due to a blend of domestic and external factors.

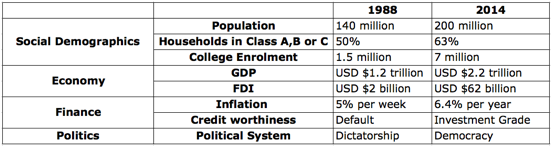

A Profound and Positive Change in Brazil Over the Last Quarter Century

Source: McKinsey and Primal Group (2015)

In spite of the headwinds Brazil faces in the short-term, the country’s future prospects remain promising. By 2050, the country is expected to overtake Germany and become the world’s fifth largest economy. Currently the fourth largest agricultural producer in the world, the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization predict Brazil will become the world’s largest foods exporter by 2020. With the world’s fifth largest population, half of which are below the age of 30, Brazil will become one of the key global markets for consumer goods.

Life has been eventful in Brazil over the last decade. The global commodities bubble peaked and subsequently burst, the country saw three Presidential elections, hosted the 2014 soccer World Cup and is now preparing for the 2016 Summer Olympics. Now that US Federal Reserve has raised interest rates to 0.5% (the first time since 2006), higher borrowing costs for developing economies may well compound the slowdown taking place across these regions and send ripples across global financial markets.

Brazil has been hit by the slowdown impacting emerging markets and commodity exporters. The simultaneous strengthening of the US dollar and slowing Chinese demand for raw materials has impacted the price of commodities, a major catalyst for Brazil’s transformation since the new millennium. In the first seven months of 2015 exports to China fell by 19%, although with foreign currency reserves of $380 billion Brazil has a substantial cushion if necessary. Adjustments still need to be made. The social polarization that has surfaced following the 2014 presidential election is now a major factor in the country’s near term future. The extensive safety net established by Rousseff’s Workers Party during the commodity boom at the beginning of this century is now under threat as government finances come under strain. By 2014 fiscal results in Brazil had worsened. The primary result has moved from a surplus of 1.9% of GDP in 2013 to a deficit of 0.6% a year later. Forecasts of a recession in 2015 may well continue into 2016. In short, the current coalition government in the country was caught out by demand adjustments beyond its borders.

Indeed, all emerging markets face a challenging road ahead. The difference with Brazil is that the country has already initiated the changes necessary to bolster growth and investor confidence. With fiscal reform lowering taxes on inbound capital flow, a persistent removal of corruption and the dawning of a more conservative era, we are convinced that Brazil will cement itself as a viable, lucrative and exciting diversification vehicle.

Whatever else ails the country, agriculture still remains its greatest success over the past near half century and uniquely one that governments have avoided interfering in. Brazil has ownership of more freshwater than anywhere else in the world, twice as much as its closest rival, and the highest amount of available farmland (300 million hectares). Already a top three producer of multiple crops and foodstuffs globally, including sugar and coffee (no.1), soybeans (no. 2) and corn (no. 3), Brazil is also the world’s largest exporter of beef and poultry. Agricultural output even doubled between 1990-2013, while livestock production trebled over the same period. Agricultural exports reached $86 billion in 2013 (36% of total). With the sector representing 5.5% of Brazil’s $2.2 trillion GDP in 2014, and utilizing an impressive 13% of the total Brazilian workforce, there’s no wonder that agribusiness in the country reached $476 billion (the value of which has doubled over the last decade alone).

And that’s the way it is with Brazil. With annual GDP reaching a record high of 7.6% y-o-y in 2010, and a 2% contraction forecast for 2015, the country represents everything attractive and challenging about the higher returns likely to come from emerging markets in the medium-long term. In fact, the country has so much potential that it is difficult to think of a more attractive developing market with more opportunity when demand picks up and the current cycle turns, as it inevitably will.